Texture is the defining element in 2010

Guangzhou TV Tower

Guangzhou, China Dubbed both the supermodel and the twisted lady, Guangzhou's

2,000-foot-tall TV tower is a woman above all: "Most skyscrapers bear

male features—they're introverted, rectangular, and repetitive,"

Information Based Architects' Mark Hemel has said. "We wanted a female

tower that is complex, transparent, curvy, and gracious." His team

created a slender hourglass of steel columns that twist into a tightly

woven "waist" 560 feet above the ground. This middle area doesn't have

floors or walls; instead, there's an open-air staircase where visitors

can see the latticework construction up close. Gusts blow through the

steel mesh in certain cross sections; elsewhere, glass panels enclose a

movie theater, two rotating restaurants, and shops.

Dubbed both the supermodel and the twisted lady, Guangzhou's

2,000-foot-tall TV tower is a woman above all: "Most skyscrapers bear

male features—they're introverted, rectangular, and repetitive,"

Information Based Architects' Mark Hemel has said. "We wanted a female

tower that is complex, transparent, curvy, and gracious." His team

created a slender hourglass of steel columns that twist into a tightly

woven "waist" 560 feet above the ground. This middle area doesn't have

floors or walls; instead, there's an open-air staircase where visitors

can see the latticework construction up close. Gusts blow through the

steel mesh in certain cross sections; elsewhere, glass panels enclose a

movie theater, two rotating restaurants, and shops.Soccer City

Johannesburg, South Africa In Jo'burg, where soccer is more religion than sport, Soccer City,

the venue for this summer's World Cup, is an appropriately dazzling

temple devoted to the worship of headers and punts. And since 2010 marks

the first time any African nation has hosted the tourney, architect Bob

van Bebber, of Johannesburg-based Boogertman Urban Edge, sought to rep

the whole continent with a multihued melting pot that would loom large

but feel familiar to fans in each of the stadium's 94,000 seats. He

modeled his 7,000-ton steel-and-concrete arena after the calabash, a

gourd that has varied uses—musical instrument, beer stein, motorcycle

helmet—and that is found all over the continent's 11 billion square

miles. Furthering the melting-pot motif is an earthen-colored exterior

set into a "fire pit" of lights. "The design was inspired by ideas about

shared experiences: drinking, pattern making, storytelling," says Van

Bebber. "We wanted to bring divided cultures together not only for this

world event but for the future."

In Jo'burg, where soccer is more religion than sport, Soccer City,

the venue for this summer's World Cup, is an appropriately dazzling

temple devoted to the worship of headers and punts. And since 2010 marks

the first time any African nation has hosted the tourney, architect Bob

van Bebber, of Johannesburg-based Boogertman Urban Edge, sought to rep

the whole continent with a multihued melting pot that would loom large

but feel familiar to fans in each of the stadium's 94,000 seats. He

modeled his 7,000-ton steel-and-concrete arena after the calabash, a

gourd that has varied uses—musical instrument, beer stein, motorcycle

helmet—and that is found all over the continent's 11 billion square

miles. Furthering the melting-pot motif is an earthen-colored exterior

set into a "fire pit" of lights. "The design was inspired by ideas about

shared experiences: drinking, pattern making, storytelling," says Van

Bebber. "We wanted to bring divided cultures together not only for this

world event but for the future." Design Museum Holon

Holon, Israel Curvaceous and expressionist, Ron Arad's Design Museum in downtown

Holon defies Bauhausian efficiencies in an area of the world molded

around that movement's strict, practical lines. Arad's brazenly

decorative design comprises five Cor-Ten steel ribbons oxidized to

different shades of reddish-orange. After wrapping around a courtyard

(shown here), the steel strips bind together to create the walls of the

museum's small lower gallery, reminding the visitor that "the building

envelope is not just a pretty space, it's a structure," says Arad. One

band swells into a ramp that connects the museum's two levels; inside,

an "immersive design environment" is punctuated by interactive and

digital exhibitions accessible through an underground entrance "cave."

As for Arad, his ultimate commission was to create a second Bilbao—an

obscure city brought to the forefront by a postcard-worthy piece of

architecture—and in this capricious rotunda of steel, he may have done

just that.

Curvaceous and expressionist, Ron Arad's Design Museum in downtown

Holon defies Bauhausian efficiencies in an area of the world molded

around that movement's strict, practical lines. Arad's brazenly

decorative design comprises five Cor-Ten steel ribbons oxidized to

different shades of reddish-orange. After wrapping around a courtyard

(shown here), the steel strips bind together to create the walls of the

museum's small lower gallery, reminding the visitor that "the building

envelope is not just a pretty space, it's a structure," says Arad. One

band swells into a ramp that connects the museum's two levels; inside,

an "immersive design environment" is punctuated by interactive and

digital exhibitions accessible through an underground entrance "cave."

As for Arad, his ultimate commission was to create a second Bilbao—an

obscure city brought to the forefront by a postcard-worthy piece of

architecture—and in this capricious rotunda of steel, he may have done

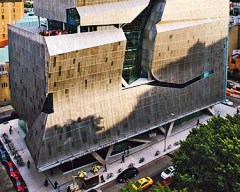

just that.Cooper Union

New York City A deconstructionist cube slashed with a jagged hook-shaped gash, the

bold new Cooper Union centers around a 20-foot-wide grand staircase that

ascends to a rooftop atrium; that glass topper also serves as a

skylight for the 175,000-square-foot superstructure (75 percent of which

is naturally lit). Home to the Cooper Union for the Advancement of

Science and Art, Morphosis's iconic design has operable insulating

stainless steel panels, radiant heating and cooling, and a "green" roof

that entitled it to an LEED Gold rating and makes it 40 percent more

energy efficient. In the spirit of Peter Cooper, who founded the

institution in 1859 to foster free access to the arts in New York, a

public gallery shows architectural exhibits and a 200-seat auditorium

hosts open art lectures.

A deconstructionist cube slashed with a jagged hook-shaped gash, the

bold new Cooper Union centers around a 20-foot-wide grand staircase that

ascends to a rooftop atrium; that glass topper also serves as a

skylight for the 175,000-square-foot superstructure (75 percent of which

is naturally lit). Home to the Cooper Union for the Advancement of

Science and Art, Morphosis's iconic design has operable insulating

stainless steel panels, radiant heating and cooling, and a "green" roof

that entitled it to an LEED Gold rating and makes it 40 percent more

energy efficient. In the spirit of Peter Cooper, who founded the

institution in 1859 to foster free access to the arts in New York, a

public gallery shows architectural exhibits and a 200-seat auditorium

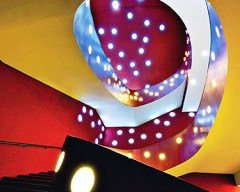

hosts open art lectures.Za Koenji Public Theatre

Tokyo, Japan Bright with neon wattage and bustling with Lady Gaga–like Harajuku

fashionistas, Tokyo is not known for subtlety. But the aesthetic is less

flashy and more fanciful on the outskirts of Suginami City, where

rising Japanese architect Yoko Ito settled on an otherworldly,

craterlike look for his Za Koenji Public Theatre. "I tried to create an

impression of an enclosed tent cabin, or playhouse," Ito says. A thin,

sheeny skin of black steel stretched over a scalloped silhouette, the

36,000-square-foot construction certainly dwarfs low-lying neighbors,

but its crenated sloped roof and dotty apertures hint at its role as an

outlet for community performing arts. Ito designed three stories and

three basements to comply with stringent height restrictions. One

concert hall is flat and flexible; another, created specifically for

rehearsals of the Awa Odori dance festival, has a revolutionary concrete

floor that bounces back from the liveliest cartwheels and steps.

Bright with neon wattage and bustling with Lady Gaga–like Harajuku

fashionistas, Tokyo is not known for subtlety. But the aesthetic is less

flashy and more fanciful on the outskirts of Suginami City, where

rising Japanese architect Yoko Ito settled on an otherworldly,

craterlike look for his Za Koenji Public Theatre. "I tried to create an

impression of an enclosed tent cabin, or playhouse," Ito says. A thin,

sheeny skin of black steel stretched over a scalloped silhouette, the

36,000-square-foot construction certainly dwarfs low-lying neighbors,

but its crenated sloped roof and dotty apertures hint at its role as an

outlet for community performing arts. Ito designed three stories and

three basements to comply with stringent height restrictions. One

concert hall is flat and flexible; another, created specifically for

rehearsals of the Awa Odori dance festival, has a revolutionary concrete

floor that bounces back from the liveliest cartwheels and steps.Calais Fine Arts and Lace Museum

Calais, France "Lace evokes those incomparable designs which the branches and leaves

of trees embroider across the sky." So said fashion goddess Coco

Chanel, who would be chuffed to see that same sky embroidery glimmering

in the glass-and-steel facade of the Calais Fine Arts and Lace Museum,

an homage to the millions of yards of frills and tulles threaded in

Calais since the early 1800s. With an exterior that looks screen printed

by a Jacquard loom's punch cards, the undulating L-shaped construction

references the northeastern French town's industrial past, when Calais

reigned as the world's lace capital. Inside, the sunlit space is filled

with fashion magazines, costumes, and lace—from the seventeenth-century

trim trendy with Louis XIV and the like to the traditional, flowery

fabric in this photo's foreground. "We wanted to pay tribute to the

generations of men and women who worked this difficult and mysterious

trade," said Alain Moatti of the French architectural firm Moatti et

Rivière. "The structure is an homage to lace—to its sensuality

"Lace evokes those incomparable designs which the branches and leaves

of trees embroider across the sky." So said fashion goddess Coco

Chanel, who would be chuffed to see that same sky embroidery glimmering

in the glass-and-steel facade of the Calais Fine Arts and Lace Museum,

an homage to the millions of yards of frills and tulles threaded in

Calais since the early 1800s. With an exterior that looks screen printed

by a Jacquard loom's punch cards, the undulating L-shaped construction

references the northeastern French town's industrial past, when Calais

reigned as the world's lace capital. Inside, the sunlit space is filled

with fashion magazines, costumes, and lace—from the seventeenth-century

trim trendy with Louis XIV and the like to the traditional, flowery

fabric in this photo's foreground. "We wanted to pay tribute to the

generations of men and women who worked this difficult and mysterious

trade," said Alain Moatti of the French architectural firm Moatti et

Rivière. "The structure is an homage to lace—to its sensualityDavid Mikael Taclino

Inyu Web Development and Design

Creative Writer

1 comments:

Being an architect, I would say these buildings are brilliantly designed! Kudos to their architects!

Paul

http://www.archability.com

Post a Comment